Shirley Benson Sacks and Pennsylvania German Star Embroidery

by Johannes Zinzendorf

When Shirley Benson Sacks died in September, 2021, just shy of her ninety-sixth birthday, she was a successful business woman, a recognized embroiderer, a craft demonstrator, a political activist, a teacher, a Girl Scout mentor, textile conservator, and the practitioner and preserver of a rare Pennsylvania Dutch fiber art. She was also a long-time friend.

She was perhaps best known for her Pennsylvania German star embroidery, a decorative applique craft that she learned from an elderly Pennsylvania Dutch woman decades ago, and then demonstrated and taught at festivals, historic sites, and craft shows throughout eastern Pennsylvania for many years.

SS 1

Shirley's longest connection was with the Kutztown Folk Festival. It is safe to say that Shirley, for many years, had an ambivalent relationship with the festival under former management. She and a fellow crafter and demonstrator had issues with festival leadership, and also resented the fact that while the festival was held in Kutztown with the support of hundreds of area volunteers, nonetheless the proceeds went out of the county to Ursinus College, for historical reasons.

As she told Reading Eagle reporter Jamie Klein in a 2013 interview, “I've really been much involved with what was happening politically at the festival. I didn't like some of what was happening. In this case, it was two little old ladies who decided things have to get better, and so we worked on it and it happened, and now we have probably the most wonderful director [Dave Fooks] in the whole world.”

So Shirley had fangs, but she could also purr as well.

Through years of organizing, protesting, and attending dozens and dozens of public meetings, Shirley gained her reputation for being a gadfly, a goad, and a thorn in the side of pompousness and injustice. She was short but tough, and could not be intimidated. She didn't suffer fools at all, and she never, ever held back in saying what she thought, even when there were times, like in the nursing home of her last years, when a little restraint may have made things go easier for her, but that wasn't Shirley.

As she described her festival involvement to Klein, “I applied to be a vendor because I had my needlework shop at that time. This was 1976 or so, and a friend of mine who demonstrated spinning and weaving said, 'Hey, you should apply and bring your stuff over'. So I did and I was. And I've been there ever since.”

Actually, there were lapses in attendance when she was on the outs with festival management, but she always returned.

“Ending with the year 2005, I was a vendor. After 2005, I'm simply there in my little spot in front of the Quilt Barn so I don't have to drag stuff and put up a booth.

“Basically, I just have a little table. You'll see me in my corner telling people about the history of the embroidery. I have some very, very old samples that I bring with me so people can actually see them, and that's what I do for the past five years or so.”

By her death, Shirley was the oldest and perhaps the most tenured participant in the festival, though by that time she'd been physically unable to attend for several years. She was actually relieved at just being able to demonstrate without having to set up a large display and sales exhibit. As she aged, she was also relieved, a few years later, when space was found for her inside and she no longer had to bear summer heat and exposure.

SS 2

Shirley was well aware of the irony of being a Jewish woman at what began as a celebration of Pennsylvania German culture.

As a business owner, she consciously downplayed her Jewish heritage because she was well aware of lingering anti-Semitism in the area. She recalled hearing anti-Semetic comments from unaware customers in her own shop, and she didn't want that to affect her income.

Her parents were English, though at least her father's people, as I recall, came from Eastern Europe. Her father may have served in the British Army, and Shirley said he also played the violin. Marty Riggleman, a long-time friend of Shirley's, said Shirley kept in touch with her father's people in England in later years and also took her daughter to visit them.

In Chicago, the family's original name was retained until Shirley's father decided he wasn't getting work because it singled him out as being Jewish. He changed it to Benson, and Shirley always signed her name Shirley B. Sacks. She was born in Chicago, but the family moved to New England to improve their economic prospects.

At some point her mother died, her father remarried, and, true to the stereotype of wicked step-mothers, things did not go well between Shirley and the new wife, who eventually had a daughter with Shirley's father but expected Shirley to take care of the baby. She left home as soon as she could but remained in New England and had a variety of jobs, including working in a five-and-dime store, as well as being a stenographer and secretary. She then met her future husband, Bernard [with the accent on the first syllable] who was serving in the Navy at the time.

He was from New Jersey, and that's where they married. He was a mechanical engineer, and later found work with a company in the Reading area. They bought a small farm with a limestone farmhouse in the foothills south of Fleetwood, and they had a daughter, Claire. Unfortunately Claire had childhood diabetes, which affected her eyesight and she eventually became legally blind. She was later accepted into a special school operated by what was then Kutztown State College. Claire also went into the Girl Scouts, which began a lifelong involvement for Shirley in the Scouts as well.

With Claire in school, Riggleman said Shirley had time on her hands and decided to open a craft store, the Crewel World, in Fleetwood as she had an interest in embroidery. And that is where fate intervened.

In her own words, and written for a publication she worked on for years but remained unfinished at the time of her death, Shirley recalled:

“My adventure with 'Star Embroidery' began with the kindness of a little old Pennsylvania Dutch lady whose name was Bertha Rauch. She lived across the street from my first shop in Fleetwood. This was the early 1970s. She knew I was interested in all kinds of needlework.

“One day she brought in a set of flower-shaped tin templates and told me that she had been taught how to do embroidery with them when she was very young. The history behind them is:

“When a wool blanket or men's suit wore out, seven- or eight-inch squares were cut from the good sections. Wool sweaters that were no longer usable were raveled out and the yarn used for the embroidery. The embroidery was done over the tin template on the squares. The squares were then stitched together to make a comforter or pillow or, with smaller pieces, for pin cushions. This technique goes back at least one-hundred years.

“Bertha very kindly shared her extra set of templates with me and I have been teaching 'Star Embroidery' ever since, from eight-year-olds to eighty-year-olds.

“My object in creating this booklet is to insure that this type of Pennsylvania German needlework is not lost.

“Whenever I pick up a needle to work this embroidery, I thank Bertha.”

SS 3

Riggleman, as Shirley's executor, has Shirley's notes for the booklet and plans to complete and print it, so the story and technique of her craft indeed will not be lost.

Shirley later moved The Crewel World to a Victorian-era brick house on Main Street in downtown Kutztown. She offered a wide variety of yarns, craft kits, and supplies. She also promoted and displayed the work of other area craftsmen, particularly the redware pottery of Gerald Yoder and the coverlets of weaver William Logan, with her shop, in effect, serving as a retail outlet for them.

She offered classes to a variety of age groups, both at her shop and at locations such as the Mennonite Heritage Center in Lancaster and many historic sites, craft shows and festivals across the region. For years, she went with Riggleman to do craft shows at Elfreth's Alley in Philadelphia.

She and I participated in many festivals, beginning in the mid-1980s, that included Landis Valley Museum in Lancaster and Bethlehem's Musikfest, and we often found ourselves sharing space at a number of historic sites. I particularly recall her at festivals held at the Alexander Schaeffer homestead in Schaefferstown. There, she was inevitably found at a table set up in the front yard teaching girls eager to try their hand at the embroidery projects she'd brought. I was always struck by how happy she was, with a big smile on her face.

The tools and supplies for her star embroidery did not take up much space in her small hatch-back, leaving room for a card table and chair. She could unload, set up, and be ready to start in minutes. I envied that simplicity while unloading large and cumbersome flax brakes and scutching wheels. And packing up and leaving, at the end of a long day, was just as easy. She was always glad to arrive, but she was always relieved to head back to her farm house as well.

Shirley was a serious crafter, and described her accomplishments in a draft for her projected book.

“I am a state and chapter juried member of the Pennsylvania Guild of Craftsmen since 1975. From 1970 until 2010, I had my own needlework business. As of January, 2014, I am listed as a craftsman in the directory of 'Early American Life' [magazine]. I also have my teacher certification in crewel embroidery from the Elsa Williams School of Needlework.”

At the time of her listing in EAL, she also had a small ad in the magazine offering free catalogs of her craft supplies and kits and got dozens of responses. She also wrote an article on star embroidery published in the magazine's Christmas issue of 2014.

Her husband and daughter were still living when I first met Shirley, but

Bernard eventually came down with dementia. Shirley cared for him as long as she could, but she eventually fell and was hospitalized, and Bernard was admitted to a nursing facility. There were issues with getting the Veteran's Administration to recognize his service since he did not serve overseas or in combat, so Shirley had to pay his nursing home bills while she fought with the VA to have him admitted to one of their facilities. That was finally accomplished, but he died soon after.

Meanwhile, Claire, who was an accomplished musician and studied the harp at the Julliard School in Manhattan, had become dependent on Shirley for support, and Shirley worried what would happen to Claire if she died first and her daughter would be left alone, but she didn't. It was Shirley who was left alone in her house, with her cat for company, while continuing a full schedule of craft shows and teaching. Eventually faced with declining sales, she moved her shop to a building further east on Main Street owned by Riggleman, and finally closed it altogether and operated out of her house. She wanted to turn a room in her house into a studio and classroom, but that never happened.

After I retired from doing craft shows and no longer saw Shirley regularly, I began visiting her occasionally and took her out to eat at the Kutztown Diner, near a small airport on the west side of town. She didn't eat much, but always had a take-out box for the leftovers and so another meal when she got home.

Shirley's physical decline was gradual but noticeable. At first, she walked unassisted to my car and into the diner; then she needed a cane, then a walker and, eventually, a wheelchair. In part, she suffered from osteoporosis, which increasingly bent her over and itself made walking difficult.

There came a time when she was unable to care for herself, and Riggleman found a place for her at an assisted living facility. Needless to say, Shirley was not happy and made her complaints loudly known and could not have been an easy resident to deal with. Still, she realized she needed help, even though that rankled her. She and Riggleman found another facility for her, this time in Kutztown, but she didn't like it either.

I visited her there, and even took her to the diner one last time, in a wheelchair. But the pandemic changed everything, of course, and I wasn't able to see her again. Even calling her became difficult. And then Riggleman called to say that Shirley had passed.

She was cremated, and Riggleman spread her ashes at her beloved farm. There were no close relatives, just some distant cousins on Bernard's side who didn't keep in touch.

She gave some samples and tools of her craft to the Hermitage where I live, which were arranged into a small exhibit in her honor. I like to recall Shirley's acid wit, her kindness, her smile, and her utter joy in teaching young girls the art of embroidery.

While Shirley was not religiously observant, I knew Jewish rituals were still important to her, and so after her death, also knowing there would be no one to say Kaddish for her, I found a prayer shawl in the Hermitage's Judaica collection, printed an English translation of the Hebrew Kaddish, and said it for her. True, there was not the minyan (a quorum of ten men) to make it official, nor am I Jewish, but I wanted to do something to remember her passing.

This short, simple prayer for the dead ends,

“May there be abundant peace from heaven, with life’s goodness for us and for all thy people, Israel. And let us say: Amen.

“May the One who brings peace to the universe bring peace to us and to all the people, Israel. And let us say: Amen.”

Dearest Shirley, rest in peace.

Shirley's Craft

In her 2013 interview with Reading Eagle reporter Jamie Klein, Shirley explained how she got involved with her craft.

“I

demonstrate Pennsylvania German star embroidery. It's very much Berks

County. It's a kind of embroidery that was done at least 150 years

ago here in Berks County.

“It

was taught to me by a lady who was born and brought up on a farm near

New Tripoli, which is north of here. At that time, my shop was in

Fleetwood, right across the street from where she lived. I was much

involved in Girl Scouts at the time. My daughter was a Girl Scout, so

they grabbed the moms, you know.

“She

was in her seventies maybe at that time, and she was cleaning out her

kitchen cupboards, and she found a whole set of patterns. She came

trundling over [with] two sets of them. She thought that I would like

to teach my Girl Scouts how to do this, and I did. That was at least

30 years ago, and I've been doing it ever since.”

SS 5

Today, Riggleman continues to teach the craft Shirley taught her to new generations, and hopes they might find new ways to adapt the style to different projects. She is also assembling Shirley's booklet for eventual publication.

In an interview, Marty explained the craft begins with a tin, six-pointed star [other designs are also possible, and even metal flashing can be used]. It is placed on strong fabric like wool. A hole is put in the center of the star so it can be attached to the fabric. The project can be placed in an embroidery hoop to secure it while working. Wool yarn is stitched twice around the perimeter of the star. Up to five colors of wool yarn are then sewn laterally across each petal. Next, the yarn is cut with scissors down the middle of each petal to the center. This releases the template which can be removed, leaving a raised yarn star.

After making a number of stars, they can be used as a form of applique to make a variety of objects, including lap robes, quilts, bed spreads, pillow covers, as decorative edging for table cloths, decorative rugs similar to hooked rugs, and, using a single small star, pin cushions or ornaments.

SS - 6

Marty continues to teach star embroidery at Wooden Bridge Drygoods outside Kuztown.

A few years ago Shirley gave the Hermitage examples of her craft, and several of the tin patterns she used, and we have them displayed in a tribute to her. We have also been able to find other examples of star embroidery that are included in the exhibit.

Illustrations

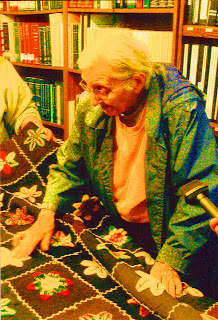

SS 1 - Shirley Benson Sacks at the Pennsylvania Folk Festival. Unknown year and date. Courtesy of Marti Riggleman.

SS 2 - Shirley at a workshop examining an embroidered star quilt. Unknown location and date. Part of the Shirley Sacks Exhibit at the Hermitage.

SS 3 - Antique tin star formerly owned by Shirley Sacks. Courtesy of Marti Riggleman.

SS 4 - Closeup of an embroidered Pennsylvania German star made by Shirley. Courtesy of Marti Riggleman.

SS 5 - Closeup of an antique Pennsylvania German star quilt from Shirley's collection. Courtesy of Marti Riggleman.

SS 6 - Another embroidered antique star quilt. Courtesy of Marti Riggleman.

The Hermitage will be open for tours from June through October by appointment by calling 570-492-4832, or via email at brojoh@yahoo.com. Our open house is Sunday, August 14, noon to 4 p.m.

SS 1

SS 1